I’ve taught myself to notice the spark of inspiration in many forms - ideas, people, a particular crackle in the atmosphere, a moral dilemma. I consciously try to live in a way where I’m exposed to these sparks. It feels healthy, uncomfortable, invigorating, intellectually necessary.

This practice is inspired by philosopher Elaine Scarry, whose book, On Beauty and Being Just, is on my Top Five Shelf. Scarry writes that “the willingness”...“to revise one’s own location in order to place oneself in the path of beauty is the basic impulse underlying education.”

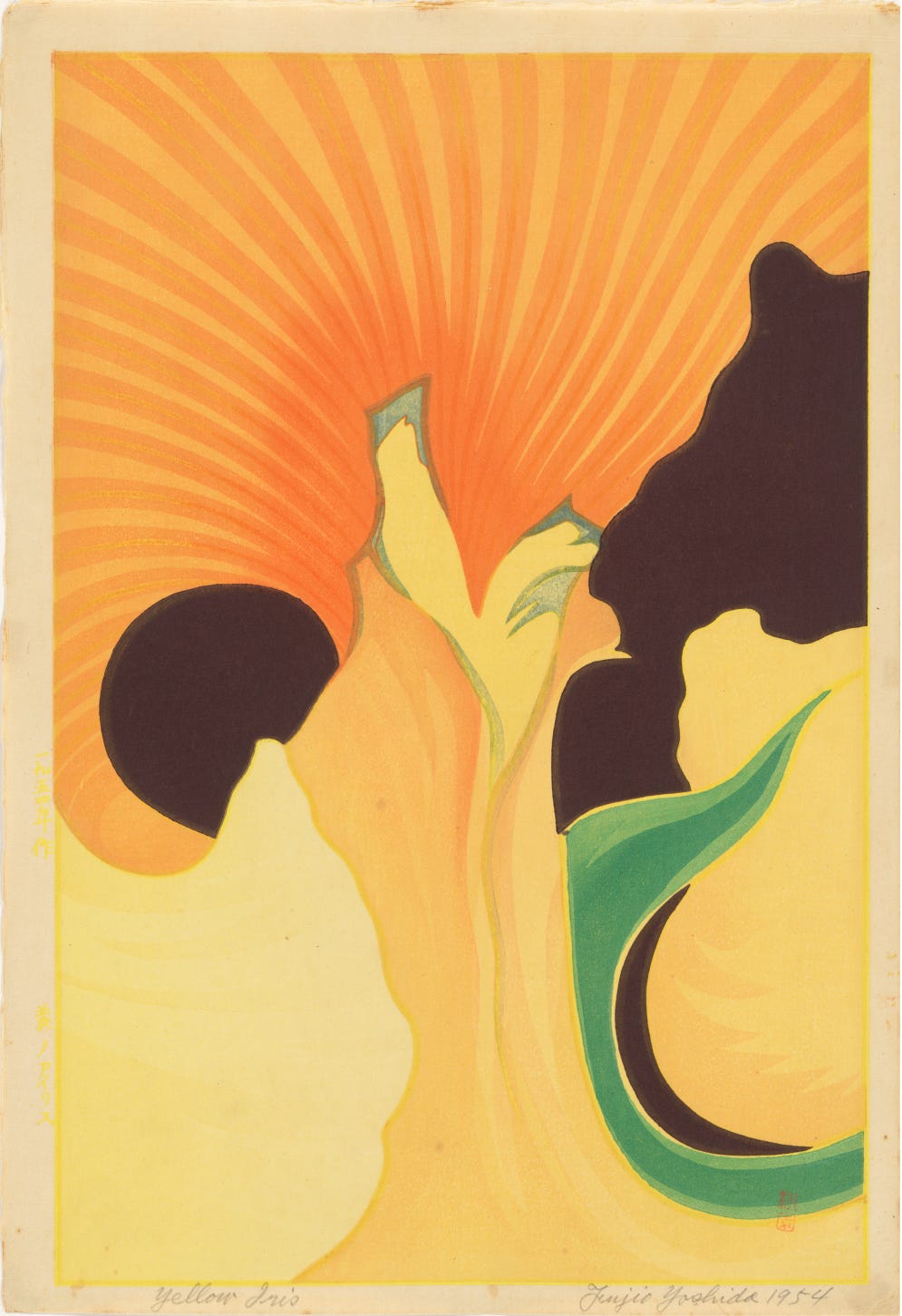

I try - as often as possible- to place myself in the path of beauty in order to learn. For me this means cracking the spines of wild books, remaining quiet in the woods, making time for museum walks, traveling with an open mind, putting on the complicated jazz, listening humbly to brilliant teachers who have put in the work, and considering possible solutions to hard problems.

Eight years ago I was focused on the particular problem of American Lawn Culture. An aspect of that problem I kept circling: how to change a predominant sensibility or cultural habit? How do you shift the American consciousness and the insecurity and consumerism behind it, in order to promote healthier and more compassionate planetary practices? (This idea intrigues me not just for addressing lawn culture, but for catalyzing larger shifts in environmental thinking and human exceptionalism - how can humans learn to de-center themselves as ravenous consumers in the planetary equation? How can I learn it myself?)

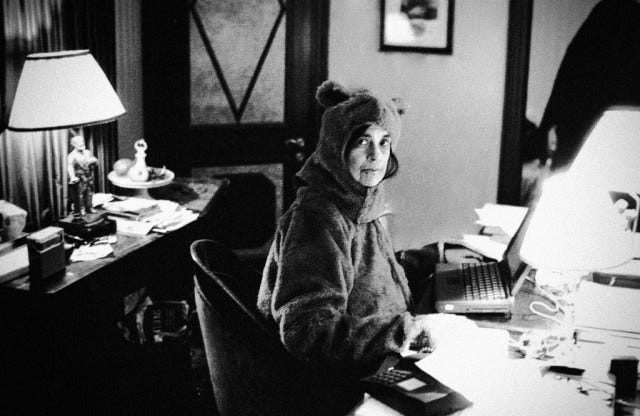

In 2016, I wrote a piece on Sontag, her concepts of Camp, and the American Lawn in my environmental column for the Paris Review:

The Great American Lawn is camp because it poisons and abuses the very thing it seeks to sentimentalize and exaggerate—nature. “Camp taste effaces nature, or else contradicts it outright,” Sontag writes. Many see working on the lawn as a relationship with the outdoors and would rather toil over an over-handled green rectangle than walk in the woods. It is not just turf grass and plastic flamingos that make a contemporary lawn camp; it is the sincere, personal investment in the creation of a prosperous image, and one that comes at a sizable personal and environmental cost.

Non-traditional beauty / liquor store outside of Savannah GA, 2024

I wondered: how many hearts and minds would I actually change with an intellectual essay on taste? Very few, I decided. So a few years later, I circled the problem again with a more straightforward journalistic piece in The Guardian:

Chances are, your lawn isn’t natural, environmentally healthy, or necessary – but it is part of a prevalent national standard. Americans spend an estimated $36bn on lawn care annually, and the amount of lawns we maintain could roughly cover the state of Florida. Lawns, not edible agriculture, are the biggest irrigated crop in America – and they are partly to blame for the decline in bees, insects and songbirds.

Why should you care? Recent studies reveal that insect numbers are remarkably low – monarch and rusty-patched bumblebee populations are both down nearly 90% in the last 20 years. Scientists estimate the arthropod population on Earth is down 45% from pre-industrial numbers. Plummeting insect populations affect everything: birds and fish can’t eat; portions of our food supply go unpollinated; entire ecosystems are at risk.

When I began the piece, I still couldn’t find what I was looking for - a macro look at human behavior and landscape, the transmission of larger ideas. These questions led me to renowned landscape architect Gary Hilderbrand. I interviewed him and incorporated some of his thoughts into my article:

Contrary to belief, one doesn’t have to sacrifice visual narrative entirely to improve environmental outcomes. “Meadows are a culturally important form, but people worry they look unkempt,” Hilderbrand tells me. “But if you mow a narrow strip along the edge, suddenly it all begins to look cared for – like you’ve intentionally let it grow long.”

Hilderbrand believes that cultural values are expressed through landscape, even at an institutional level. He points out that many lawns have cultural importance and intention, but can still incorporate sustainable methods like stormwater storage, improved soil ecology, drought-tolerant landscaping and native meadows.

He asks me to consider the public realm: downtown blocks, city tree plans, communal greens. As citizens, we don’t just notice what we see in these spaces, but how they make us feel. If we’re able to create attractive and sustainable landscapes in public spaces, the aesthetic may inform personal taste. This is how lawn culture arose, and how it can shift again, ideally to a more sustainable practice.

Hilderbrand believes in sharing images of like situations elsewhere in order to raise someone’s appreciation for what a landscape can become. It is, he says, like giving people a new set of eyes.

I began following Hilderbrand’s work, and that of his colleagues at Reed Hilderbrand. I felt as though every time I looked at a large-scale landscape project - Longwood Gardens, Storm King, college campuses - Reed Hilderbrand was involved. I realized that the meadow I’d become so sentimental about on the Bennington College campus - watching it fill with the bioluminescence of fireflies each June - was the product of the firm’s vision and work.

Gary wrote an essay in 2014 called On Seeing, where he offers a little more on the firm’s way of looking at projects and grounds:

Observers have said, generally by way of praise, that our firm’s work looks somehow inevitable—that qualities one may see in a project seem to reflect a distilled, resonant fit with particular conditions of a site. As if there were no other plausible answer—or, that we just make it look easy. It’s not.

At the Beck House, reserved and understated qualities in our work are undeniable and fully intended. We usually aim for that: an edited, essential spatial order, which emphasizes characteristics—obvious or latent—a site may already possess, or which allows for the more palpable experience of selected and specific qualities that derive from the site’s geography, microclimate, orientation, or configuration. We pursue this result from a belief in the power of design to turn ordinary characteristics into extraordinary experiences. We also seek it through an unapologetic attachment to the observable phenomena of nature—light, shade, color, scent, moisture, warmth and energy, growth and decay, seasonal change, maturation, senescence—coupled with a drive to make those phenomena apparent by allowing certain characters to come forward.

I regularly teach an Advanced Non-Fiction class at Middlebury called Landscape & Memory. I push my students to think about the flow between person and place, and how to create a multi-sensory experience on the page. (to quote Gary above: decay, seasonal change, maturation, senescence. How do we replicate that at the line level?).

By good fortune, I welcomed Gary to the class last week to hold forth and answer student questions. Unsurprisingly, the minute he began to talk, I found myself opening my notebook to jot down notes that felt essential, life-giving. This is how I know I’m in the path.

We spoke about the National Mall - our “symbolic front yard of collective ethos” and place-based visual narratives, places of witness. Gary spoke beautifully of “trees with standing,” scenic culture and the Hudson River School of Painters, Olmsted and temporality, and Emerson’s call to “realize yourself.” I couldn’t write fast enough in my notebook, and this weekend’s reading includes some transcendentalism:

“Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.”

“Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.”

“Insist on yourself; never imitate.”

-Emerson, Self-Reliance

Gary Hilderbrand is a practitioner and a teacher - and in that way is shaping landscape culture and our experiences on public and private lands in meaningful ways, now, and in generations to come. How lucky are we that we have thinkers like Gary and his team behind the wheel - people who are deeply studied and well read, who think compassionately about the complexities of land ownership and climate stewardship and cohesive national narratives, all at once?

Wishing you all a safe passage through these next weeks, which are sure to be heart-wrenching and difficult. May we all find ways to show up authentically and powerfully.

xo

MMB

*

I’d like to celebrate a sophisticated op-ed which came out of my writing workshop. Annika Hedberg wrote a brilliant piece on the EU’s Sustainability Agenda, sustainable prosperity, and why we should read the Agenda here, too.

At the close of the year, I’ll be adding the latest installment to my workbooks for paid subscribers. This last workbook will be focused on Negotiating a Relationship with Beauty.

I am closing my books for a bit to finish some editing and grading, but at the start of 2025 I’ll open back up for manuscript consults. I’m sorry that I couldn’t respond to all demand, but as I can, I will.

Shop MMB’s books here.

Thank you for these wise words during such a tumultuous time.